Throughout history, theatre-makers have negotiated societal censure and state action when staging the political – from their content being controlled, their form and aesthetic choices being policed, their bodies in performance being monitored, and more. And yet – or may be in part because of this – theatre has always been a site of active resistance. ‘Curated Conversations’ takes a deeper look at all of this.

“I like loyalty to one’s own practice but disloyalty to the form it takes.”

– Amitesh Grover

As a part of Curated Conversations, curator and creator Nikita Teresa, and interdisciplinary artist Amitesh Grover discussed the changing landscape of theatre and performance in the digital age.

Grover sees himself as a performer, director, writer, and curator depending on what the project and its form demands. As an artist, who is self admittedly disloyal to form, Grover describes himself as a conceptual artist who dwells upon what disturbs and irks him, eventually leading his art to find its form. Being in the theatre as a young person, he says, changed him and therefore, it will always be his first love.

Though his art has transcended the theatre, the art he creates is performative in nature, although, this may not always be obvious. ‘Performapaedia’ (performance-encyclopedia), a neologism coined by Grover refers to the knowledge hidden within performance systems, the radicalities, the experiences that can’t be felt in the absence of performance. His project on Sleep (I, II, III) is an example of this where he explores sleep as a personal phenomenon, entwined with the political and social phenomenon of sleep encompassing the exploration of soundscapes, capitalism, and histories. To describe where performance lies, he presents performance as a political exercise of control over the body. When performance is politicized, it connotes control over the body. Here, the desirable body of that time stands in opposition to the undesirable body and it is in this tension where performance lies, he says.

Grover described himself as having been part of a crossover generation that was caught in between India transforming from a socialist to a capitalist society. He recalled seeing a 2 kilometer long line when the first McDonald’s opened in Connaught Place in Delhi and instantly felt that he did not belong to this time. He views his practice as a record of what is and what was, exploring how we remember rather than what is remembered by history.

When asked about his process, Grover says he spends much of his time daydreaming because reality is dissatisfying. His work reflects his desire to get up and change it even if only a little bit. This triggers his interest in everyday rituals for in them, one finds unsayable knowledge that can’t be contained in text and needs to be performed. He states that everyday bodies are performing bodies. In a performance, he believes, performers and spectators are interchangeable categories. Here, performance is seen as an invitation to tease out information – When talking about the mundane as performance, he says that it is to “lay siege on the everyday”.

Art, he says, is more accident, failure and frustration, than success. And so, he shares, he ruminates over an idea for almost a year or two to make something. He admits he loves writing manifestos where he defines the project for himself. Filling it with instructions, pointers as if marking the territory, or as he described it, pagdandi of the project. This guides the labour aesthetics, ethics and form the project takes. While the manifestoes he writes are for his personal clarity, over the years, curators have displayed and published the manifestoes as a piece in and of themselves. He now realizes manifestoes in actuality are public documents – they are performative calls to action. Recently, he began gravitating toward labour-intensive projects. For example, for the last 3 years, as a part of his bill board project, he has been writing everyday, much like a cartoonist drawing for the next day’s paper.

Building worlds, archives and manifestoes

Grover likes to build an archive for each project containing bits and pieces – the process of making it, audience reactions across media, pictures, bits of writing etc. He also produces a bibliography for each project. This archive is also complete in itself and is invited to be presented stand-alone. In the past, these archives have invited the audience to interact with it through taste, touch and sound. This interaction with the archive adds to the archive, and relates to the idea of ‘performopedia’.

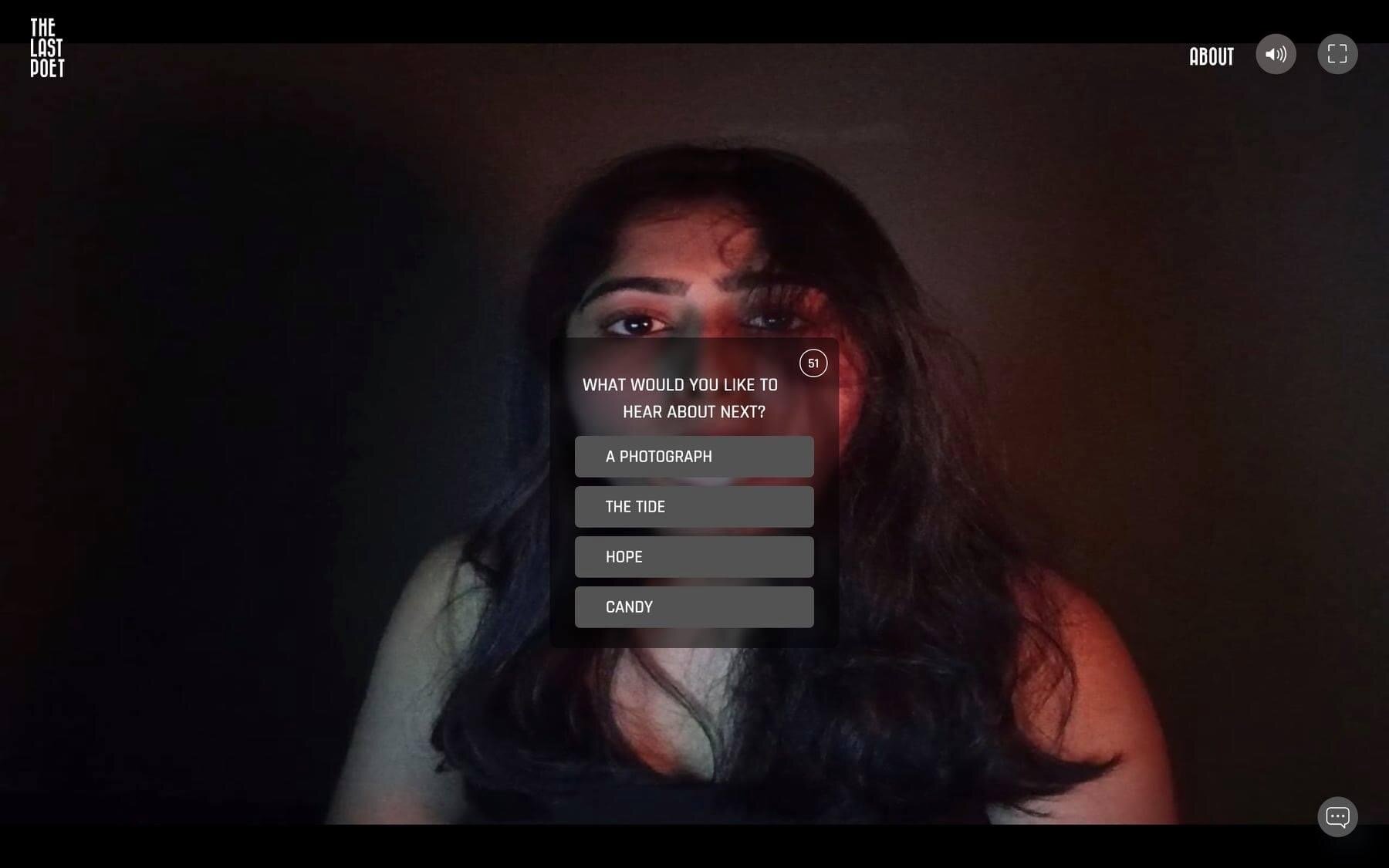

When asked by Teresa whether there is a space for actors in ‘performapaedia’, Grover shares he used actors in one of his most recent works, The Last Poet, an interactive piece online that came from the pandemic. He acknowledges that actors are central to his piece but when he uses actors, they are a part of a much larger project and he, as a director, must prepare his vision first before calling on the actors. Making a performance work is a world building process and is not limited to just the text and the actor.

Grover’s work ventured into the online space and new media, even before the pandemic happened. When asked what triggered him to do so, he says it was his dissatisfaction with institutions that led him to seek out other spaces, the online space being one of them.

When describing the state of online performances in India, he says that we continue to view it as a substitute for live theatre and that webcasts are not works of theatre. We, in India, need to gradually arrive at a place where we create a separate and new space for this work, a new way of talking about it, and watching it. When creating works in the online space, one bears the responsibility of telling the audience how to watch something. Online performance competes for real estate with other sources of online entertainment like social media and OTT platforms. And yet, even as they compete for space, Grover’s online works such as The Last Poet do not seek mass appeal. What makes him uncomfortable with a work that has mass appeal is personal preference that he explains as a trade between intensity and access wherein the more intense a piece, the less access it has and vice-versa. With mass appeal also comes the shedding of context. Despite being abstract his work is specific and grounded in nature. Therefore, the mass circulation and/or appeal at loss of context is a counterproductive process.